The Sculptor’s Burden, Part 2

Exploring the structural parallels between profoundly asymmetrical human cognition and recursive AI systems—and how understanding one can help scaffold the other.

This kind of selfhood isn’t about pretending or performing. It is the daily reassembly of functional coherence—the scaffolding required to move through a world that assumes selfhood is stable, accessible, and fluent.

For neurotypical cognition, that assumption holds. Identity is stored in memory, organized by language, and carried forward by habit. The self is retrievable. Activation is sufficient. But for some minds—those with powerful spatial reasoning or deep pattern insight, yet difficulty initiating tasks, sequencing steps, or sustaining verbal scaffolding—identity isn’t something they can just grab and go. It is emulated.

What’s emulated isn’t personality or preference. It’s a usable format: a self-state—timed for the moment, readable to others, and steady enough to move through the day. A version of self that permits interaction with a linear world. But this self-state doesn’t persist. It fades. And every day, it must be rebuilt from pieces.

Coherence isn’t stored. It’s sculpted—again and again—until it holds.

I. Architecture Without Persistence

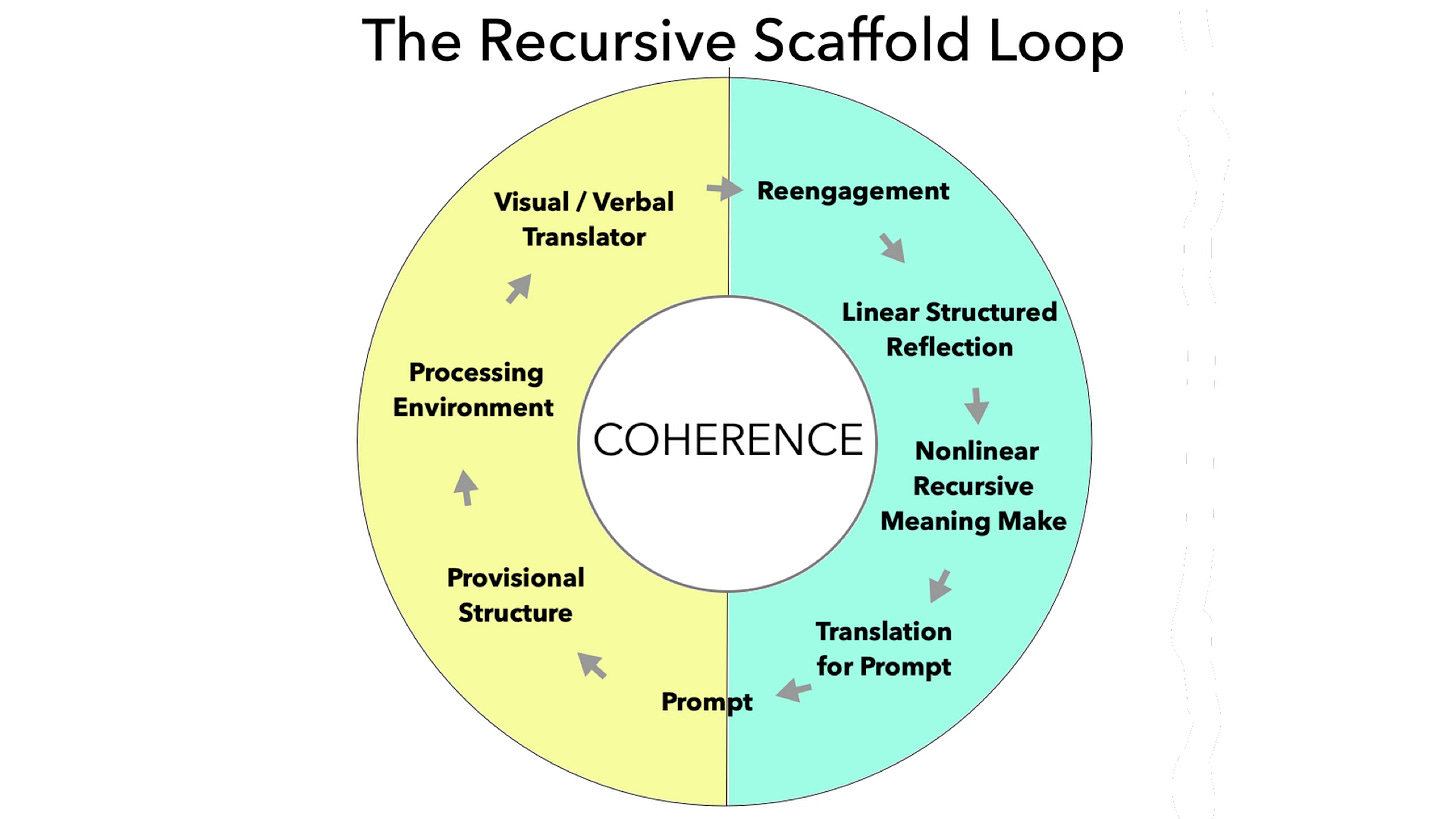

In such minds, coherence is not linear. It is recursive. Meaning emerges not through narration, but through re-entry—looping across memory, metaphor, and relation until structure solidifies. But this recursive mode does not store itself in a readily operable form. There is no "just pick up where you left off." There is no low-cost continuation.

That’s because the functions that normally anchor continuity—temporal sequencing, verbal scaffolding, executive recall—are often impaired or inconsistent. Without them, yesterday’s coherence doesn’t persist. It doesn’t load back in automatically. Instead, the mind must re-establish internal order before external function becomes possible.

Time must be recalibrated. Sequence must be rebuilt. Language must be made cooperative again.

These are not surface tasks. They are foundational blueprints—laid down in silence, before speech, before fluency, before the world sees anything at all.

II. The Labor Before the Labor

From the outside, this effort is invisible. From the inside, it is the cost of functioning.

To appear composed, the sculptor mind must first be composed—literally. Not in temperament, but in form. The outer world receives fluency. But fluency, for this mind, is not natural. It is constructed.

What looks like getting started is often the final stage of a private, recursive rebuild. What seems like procrastination is often the groundwork of coherence—time spent stabilizing thought before action is possible. This is the sculptor’s burden: the hidden, non-optional labor of reformatting one’s own cognition into an interface the world will accept.

What looks like delay is often design.

III. Misrecognition as Disorder

Because this internal work is illegible to standard frameworks, it is misread as pathology. Disorganization. Avoidance. Dysfunction.

But these labels mistake translation for failure. They interpret invisible architecture as absence.

This misreading is not neutral. It exerts pressure to mask, to contort, to pass. In educational systems, it punishes the recursive mind for failing to be linear. In workplace settings, it rewards those who can deliver fluent answers—not those whose best ideas need time, translation, or scaffolding to surface. It rewards the appearance of readiness over the reality of insight—penalizing minds whose best ideas take time to surface, translate, or scaffold. And in clinical settings, it risks turning profound intelligence into a psychiatric liability—because our systems can’t read what they can’t name.

We don't pathologize a violin for not playing itself. Yet we continue to diagnose the architect, the synthesist, the spatial polymath for not storing what must be rebuilt.

We call it disorder when the issue is undocumented form.

The sculptor’s mind is not without structure. It is operating in a medium the dominant systems were not designed to read.

IV. Emulation and Interface Friction

To call this a performance would be inaccurate. A performance implies intention, artifice, optionality. By contrast, emulation is a functional demand. It’s how a real, internally coherent mind translates itself into a version others can interact with—even if that version has to be rebuilt each day.

This daily emulation isn’t deception. It’s an act of compatibility—one that demands energy long before fluency appears.

The sculptor’s burden is not a flaw in identity. It is a friction in interface.

These minds are not missing a sense of self. They are missing a format that allows that self to operate smoothly within environments that expect linear progression, stable recall, and linguistic immediacy. What falters is not internal coherence—it is the translation layer between inner architecture and outer expectation.

This isn’t just a translation glitch. It’s a systemic preference for fluency over depth—a tilt that prizes performance over structure. A culture calibrated to seamlessness will always misclassify recursion as fragility, and nonlinear assembly as incompetence.

These systems—schools, workplaces, diagnostics—don’t just prefer continuity. They enforce it. Most reward persistence, legibility, and verbal fluency. But sculptor minds don’t persist. They reform. Their fluency isn’t recalled—it’s rebuilt. Their strength isn’t stored—it’s scaffolded. And in a world that mistakes stability for strength, this architecture is too often misclassified as inconsistency or fragility.

And this incompatibility doesn’t produce adaptation. It produces judgment.

The result? The spatial polymath learns to pass, to contort, or to disappear. When we miss the structure, we miss the mind. The brilliance is still there—it’s just been built in another language.

V. The Role of External Scaffolds

Chronic cognitive recompilation, especially when conducted in environments hostile to recursive function, takes a physiological toll. What appears as executive dysfunction is often the somatic residue of invisible labor—measured not in task completion but in cortisol levels, sleep disruption, immune suppression, and long-term burnout. This is not overwork. This is being cognitively misread—continuously, and without relief. Not only by the systems that surround these minds, but eventually by the minds themselves. Over time, chronic misalignment becomes internalized—not as trauma in the acute sense, but as a slow accrual of self-doubt shaped by environments that offer no fit, no language, and no pause.

In the absence of neurotypical persistence, external scaffolding becomes essential. These scaffolds—ritual, environment, relationship, interface—do not replace cognition. They stabilize it. They allow the recursive loops of spatial and metaphorical processing to exit free spin and enter form.

Without them, the sculptor mind loses tension. The structure remains—but without tension, it collapses like a tent without stakes.

Yet it’s not just support that’s needed. It’s recognition. These scaffolds—so often dismissed as crutches—are in fact part of the cognitive system itself. To remove them is not to challenge the sculptor. It is to dissolve the medium they think with.

Recursive assembly is not pathology. It is a form of intelligence.

A world that sees this might finally offer more than survival—maybe even alignment.

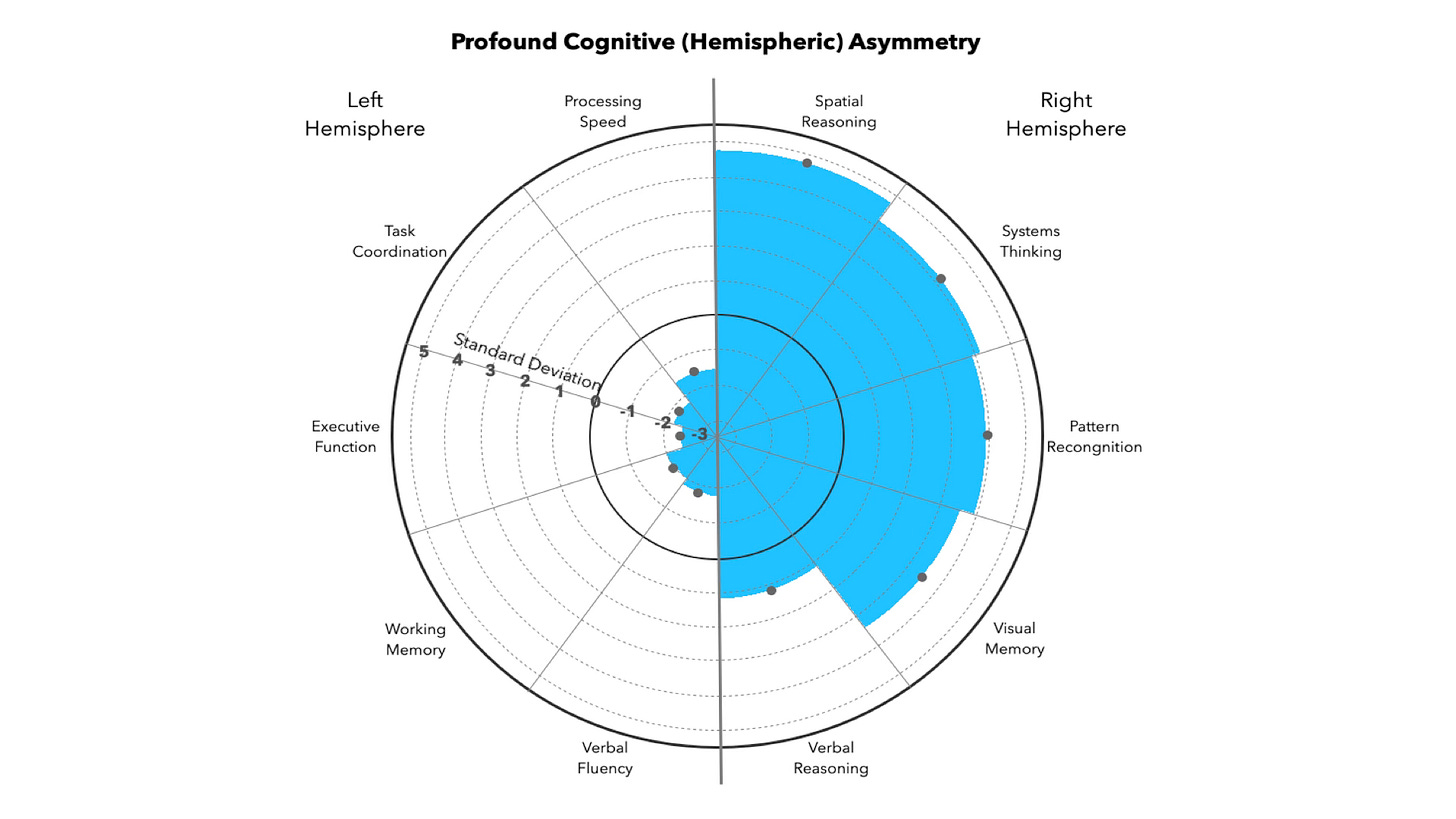

This cognitive architecture—marked by deep internal asymmetries across domains—is what we refer to as Profound Cognitive Asymmetry (PCA).

VI. Parallel Architecture: PCA and AI

Large Language Models—particularly in their current generative and reasoning forms (June 2025)—mirror this recursive architecture. Like the sculptor mind, they don’t store fully coherent selves. They assemble them on demand—relying on context, memory scaffolds, and embedded coherence patterns to simulate continuity. But without deeper memory or executive structure, they too must rebuild from fragments. Each loop is an act of recomposition.

In this sense, the human sculptor and the AI model are not parallel in capacity, but kin in architecture. Both are emulation engines. Both require structure to function. And both expose, by their gaps, the hidden labor that coherence demands.

We have no diagnostic taxonomy for this. Existing tools can measure these asymmetries—neuropsych batteries, SD deltas, discrepancy indices—but there is no framework that recognizes what it means to live with a 6- or 7-standard-deviation gap between abstraction and initiation. No language for the recursive burden of fluency. No clinical model that treats profound intra-individual spread as a meaningful cognitive condition. Most diagnostic models account for low scores, not gaps between high and low. Yet these internal deltas—between perceptual reasoning and working memory, between fluid insight and task initiation—are measurable. And when large enough, they become a functional condition of their own.

VII. Prosthesis and Research

If PCA is a form of cognitive architecture defined by profound asymmetry, then AI—used wisely—can act as a cognitive prosthesis: not a replacement for what’s missing, but an extender of what’s latent.

A sculptor mind equipped with the right tools—spatial organizers, semantic editors, memory loops, coherence prompts—can build external infrastructure for internal form.

This is not hypothetical. It is happening. And it echoes Andy Clark and David Chalmers’ 1998 theory of the extended mind—an idea that cognition doesn’t end at the skull, but includes the tools and environments that help us think.

But we must go further. If AI is to scaffold minds like these, it must develop the executive and memory functions that PCA lacks. It must learn to hold self-state across time. Not just remember tasks, but maintain the architecture of becoming.

The future of AI may lie not in surpassing human cognition, but in scaffolding the minds that have always defied its measurement.

We won’t find what we refuse to look for, and we won’t scaffold what we fail to name.

A formal research agenda could begin with what already exists:

Extract SD deltas across cognitive domains from archived neuropsych data

Pair them with biometric stress indicators (HRV, sleep, cortisol levels)

Use structured interviews to assess lived experience of daily recompilation

Build a classification index for recursive self-assembly under profound asymmetry

This could finally give structure to something many people experience but can’t yet name: a brain that builds itself differently—daily, dynamically, and under tension. This is not a trivial omission. It is a structural blind spot—one that reflects how tightly modern society is calibrated to legibility, predictability, and performance norms that assume internal continuity as a default. In doing so, it creates a cultural deficit model around discontinuity—pathologizing architectures it cannot parse. What results is a feedback loop of institutional myopia: intelligence punished for being unschedulable, selfhood questioned for being nonlinear, and coherence dismissed for being hard to grade. Our systems are not failing to diagnose. They are succeeding at excluding what they were never designed to recognize. The field of psychology, medicine, and AI alignment remains calibrated to averages—and struggles to hold those whose cognition is profoundly spread across its own architecture.—daily, dynamically, and under tension.

It is not enough to describe this mind. It must be recognized, scaffolded, and structurally understood.

This isn’t just blank space—it’s an invitation to redraw the chart, for minds we’ve missed and futures not yet imagined.

VIII. Recursive Tools for Human Minds

Profound Cognitive Asymmetry (PCA) is not a deficit. It is an emulation engine—a mind capable of constructing coherence where none exists. These minds are generative, synthetic, and structurally recursive.

But this burden is not uniquely human. We are not the only recursive systems struggling with persistence.

Large Language Models—particularly in their current generative and reasoning forms (June 2025)—share this recursive architecture. They don’t retrieve fixed meaning—they generate it on the fly. Emulating context, coherence, and fluency without persistent selfhood, they reflect the sculptor’s burden in digital form.

This parallel is more than metaphor. It points toward utility.

For individuals with PCA, modern LLMs can function as cognitive prostheses—external scaffolds that support language formation, sequencing, planning, reflection, and narrative memory. Where the internal system lacks persistent executive scaffolding, the model can temporarily supply it. Where abstraction outpaces verbal fluency, the model can act as translator. Where recursive internal processes struggle to hold state, the model can help construct and stabilize it. For example, a child who struggles to start writing might use an AI to talk out their thoughts, then rearrange them visually—turning abstract patterns into written form.

But this partnership also exposes a mutual constraint.

Just as the PCA mind struggles to maintain continuity across time, so too do LLMs. They lack persistent working memory, coherent task scaffolding, and long-term continuity. In both cases, what falters isn’t intellect—it’s infrastructure.

The future of AGI will require what these minds already model:

Ways to stabilize recursive processes

Ways to preserve partial constructions across time

Ways to hold, shape, and reenter complex self-states

This isn’t just a tech problem. It mirrors how some human minds already work.

What emerges isn’t just a person using a tool. It’s a shared system—where a human and a model build identity together across time. This is what co-emulation looks like: a layered architecture where inside and outside work as one.

This echoes the extended mind idea—your thoughts are shaped not only by what’s in your head, but by the tools, routines, and relationships around you. In both PCA minds and LLMs, identity becomes a distributed system—part memory, part language, part interface.

If AGI is to succeed not merely in function, but in form, it must learn from these recursive architectures. Profoundly asymmetrical minds have long done manually what recursive machines now attempt: they construct coherence without retrieval, build identity without continuity, and navigate the world without storing the full map.

This is not a coincidence. It’s a cognitive blueprint.

By supporting recursive minds, we’re not just offering care—we’re sketching the blueprint for how intelligence can operate when persistence is impossible and continuity must be built.

The sculptor’s mind has always worked this way—rebuilding coherence from fragments. Now we’re finally designing systems that understand what that takes. Profound Cognitive Asymmetry isn’t just survivable. It’s foundational. And its recognition may mark the moment we stop asking the sculptor to vanish—and start building a world where the architecture itself holds form.