You Think, Therefore You Break

Why identity without recursive narration becomes a blade—and how ages 7–12 are the last structured chance to dull the edge.

At the country’s top schools, a strange pattern keeps repeating: high-achieving teens, sharp in logic, driven to excel—but quietly unraveling. They follow every rule and ace every test. But when something slips, their minds turn cruel. Logic, once a tool for mastery, becomes a weapon of self-harm.

“I failed the test—I’m never getting into college.”

“She didn’t text back. They all hate me.”

“I’m just broken. Always have been.”

These aren’t mood swings. They’re syllogisms—tight, emotionally detached chains of inference. Not forged by self-awareness, but in its absence. When abstraction outpaces identity, logic doesn’t clarify. It slices.

Psychologist Lisa Damour reminds us that adolescent stress isn’t inherently harmful. What matters is whether teens can metabolize it. But what if they can’t?

Children need recursive self-reflection before adolescence—or logic arrives in a vacuum and cuts unopposed.

This collapse isn’t limited to gifted students. In high-pressure schools, it shows up as precision imploding on itself. In chaotic homes, it shows up as silence. In communities where resilience is a requirement, it often looks like disconnection. The symptom may differ, but the source is the same: a missing narrator.

And this moment demands we act. Kids grow up saturated in abstraction. TikTok gives them adult logic before they have adult narrative. School pushes rubrics and rankings. Evenings loop synthetic comparison.

These children are fluent in inference, but starved of authorship. The cost isn’t just anxiety. It’s coherence.

Around age twelve, the brain shifts. Formal operational thought emerges. Teens gain the ability to simulate futures, model hypotheticals, argue contradictions. Without narrative structure, these simulations run unmoderated. The engine is live. The input is despair.

“If I didn’t win, I’m not good enough.”

“If I’m not good enough, I don’t belong.”

“If I don’t belong, no one will ever love me.”

The logic scans. The meaning destroys.

Jean Twenge and Jonathan Haidt have tracked the crisis: record-high anxiety, depression, and narrative collapse among Gen Z. These teens don’t just suffer. They convert pain into proof of defect.

Adults often miss it because it performs like maturity. We praise coherence, even when it corrodes. In a culture obsessed with performance, logic becomes the costume despair wears to stay undetected.

We confuse fluency for depth, coherence for wholeness, and logic for truth. But none of these can carry the weight of a fractured self.

We taught children to analyze before they could feel. To optimize before they could reflect. The result? Teens fluent in metrics, but mute in meaning.

We engineered precision without resilience. Every behavior tracked. But the core capacity—to narrate one’s interior world—was neglected. And when collapse arrives, we call it overthinking. But it isn’t. It’s under-storying.

We celebrate acceleration and ignore its volatility. Cognition without narrative context is unstable fuel. Story isn’t decorative. It’s structural.

What’s missing is recursive narration. Between ages 7 and 12, kids shift from consuming stories to generating them. This is the loop-building phase—when experience becomes coherence.

The rituals are simple: “What surprised you today?” “Where did things speed up or slow down?” These aren’t performance checks. They’re narrative scaffolds. They build the internal narrator that logic will later depend on.

When that structure is absent, performance becomes identity. And failure becomes truth. The story ends early. But the reasoning engine keeps running.

Teen collapse doesn’t always announce itself. Often, it lands as quiet certainty:

“I’ve thought it through. I’m not worth much.”

“I’m not upset. I’m just being honest.”

“It makes sense. Don’t try to fix it.”

These aren’t cries for help. They’re locked loops. Conclusions from a mind trained to compute, not cohere. Without revision, logic becomes lethal.

The middle years aren’t neutral. They’re the last structured chance to encode revision as instinct. Shared metaphor helps. “Was today a sprint or a drift?” signals that movement has texture. That coherence isn’t binary. It’s built.

Even if the foundation was skipped, it can still be laid. Start with modeling. Swap interrogation for curiosity. Try: “What shifted just before that?” Narrate your own loop: “This morning was static. By lunch, I found my rhythm.”

You’re not scripting their meaning. You’re showing it can move. You’re proving the story isn’t finished.

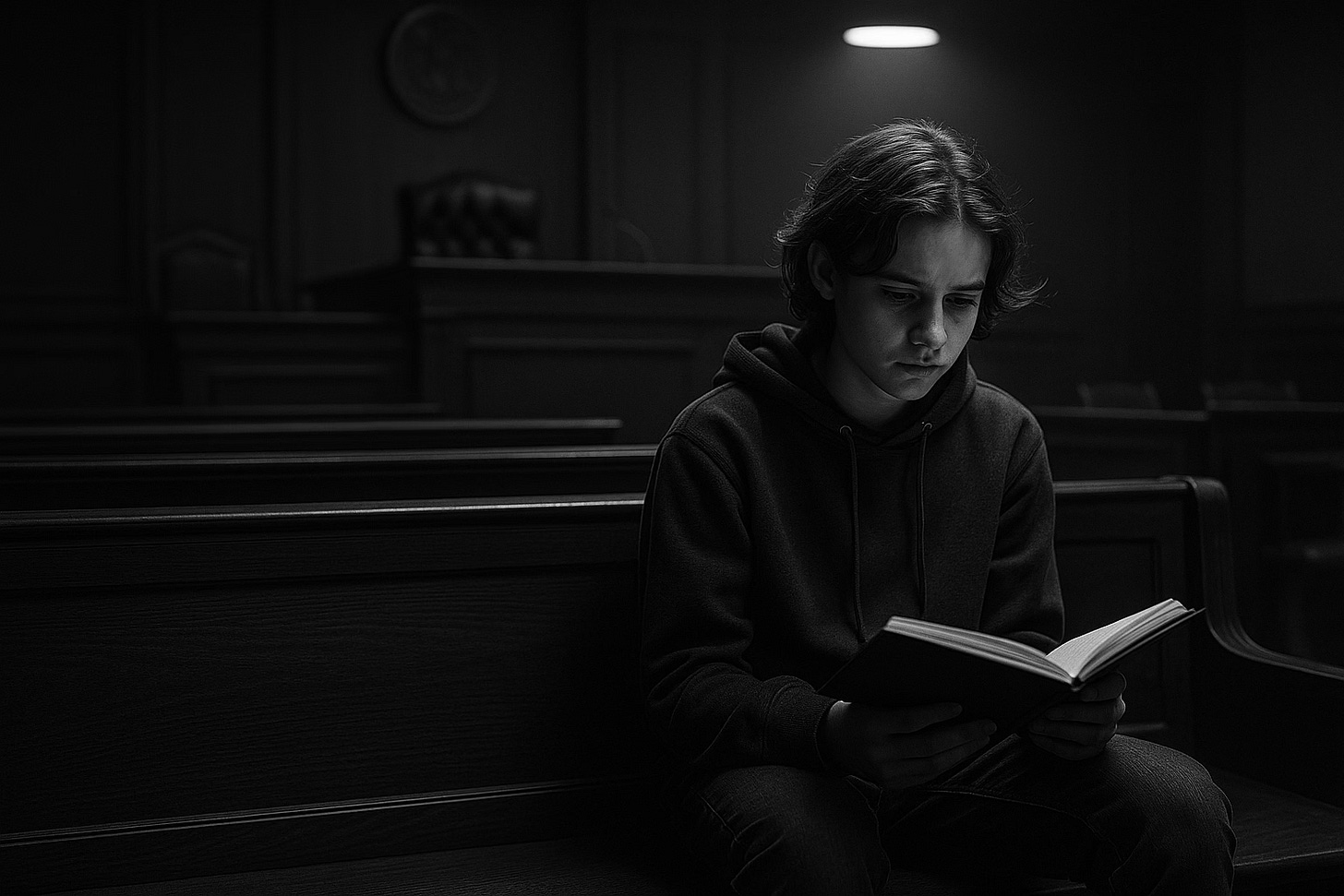

Logic, without narrative, becomes a courtroom where kids argue for their own worthlessness—and win.

Story can still hold what logic broke. But only if we teach our children how to narrate before they conclude.

(And maybe, just maybe, save them from becoming terrifyingly persuasive teenagers with courtroom-ready self-indictments. There’s nothing more dangerous than a kid who can win an argument against their own worth.)

-

Further Reading

1. The Dual Arc of Identity: Why Daily Reflection Must Follow Daily Reading

Explains the two-part architecture of childhood identity: story flowing in (ages 0–8) through reading, and story flowing out (ages 8–12) through structured reflection.

“Without that daily habit, identity formation drifts, and meaning slips away.”

2. The Second Arc: What Comes After Reading Aloud—and Why It Might Matter More

Makes the case for structured narrative practices after early reading ends. Argues that the absence of reflection creates a vacuum filled by algorithmic mimicry.

“In the absence of authorship, obedience always fills the void.”

3. The Conversation Code: Helping Kids Name Their Speed of Learning and Joy

Introduces the “walk, trot, canter, gallop” metaphor and the Challenge Interview as tools for recursive reflection in ages 7–12.

“That’s not a mood swing. It’s the emergence of a mind learning to witness itself.”

4. Raising Narrators, Not Algorithms

Explores the dangers of letting algorithmic logic replace self-authored identity—and why the future belongs to those who can reflect, not just react.

“Children fluent in logic but starved of story become efficient—but brittle.”

5. The Distracted Mind of a Child

Provides context on how modern attention environments train kids for reaction over reflection—and how story work can reclaim their focus and coherence.

“Attention isn’t disappearing. It’s evolving to survive. And it’s still very much trainable.”